Attorney: Don’t blame Jean Peters Baker for politicizing 'highly unusual' DeValkenaere case, Gov. Parson

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — Missouri Gov. Mike Parson accused Jackson County Prosecuting Attorney Jean Peters Baker of politicizing the case against the former Kansas City, Missouri, police officer Eric DeValkenaere in a radio interview earlier this week.

Posted: 4:08 PM, Nov 17, 2023 By: Tod Palmer

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — Missouri Gov. Mike Parson accused Jackson County Prosecuting Attorney Jean Peters Baker of politicizing the case against the former Kansas City, Missouri, police officer Eric DeValkenaere in a radio interview earlier this week.

“It’s a time when there was a lot of civil unrest and the problem is you don’t ever want anyone convicted because of the political side of things,” Parson said, according to a clip of the interview. “But she’s been a poor example of setting the stage and making this more of a political issue when she should be doing what’s right by the law.”

Peters Baker's office declined to comment this week following the governor's radio interview.

But does the reality of the case against DeValkenaere, who was convicted in November 2021 of two felonies in Lamb’s death, support Parson’s view?

Certainly, Baker waded into the politics of DeValkenaere’s conviction for shooting and killing Cameron Lamb on Dec. 3, 2019, in the driveway of his residence in the 4100 block of College Avenue.

She sent a letter to Parson urging him not to pardon DeValkenaere and inserted her office into the appellate case when the Missouri Attorney General’s Office refused to defend the verdict, but that came well after his four-day bench trial and conviction for killing Lamb.

Those moves also were partly in response to the unprecedented decision by the AG’s office not to defend the conviction her office won at trial — an overtly political twist in the case.

In fact, one prominent criminal defense attorney in Kansas City believes the case became politically charged from the outset as KCPD moved to protect one of its own rather than by Baker as Parson asserted.

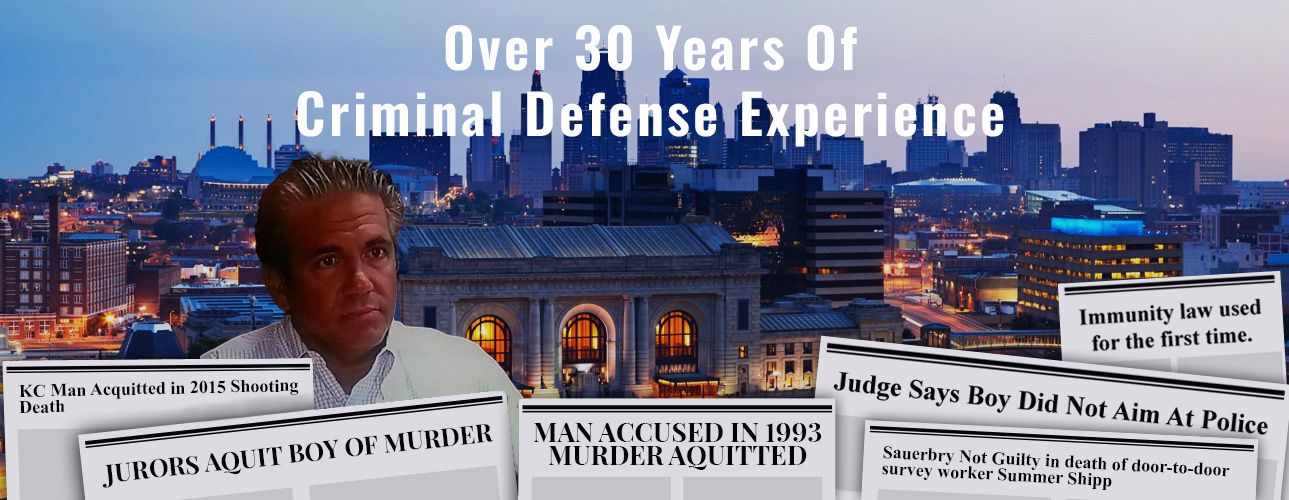

“I don't think it's fair to say that Jean Peters Baker is anti-police,” attorney John Picerno said in an interview Thursday with KSHB 41. ”I think she takes her job very seriously. She prosecutes 1000s of people every year, day in and day out. Law enforcement officers testify for Jackson County prosecutors, her employees, every day and they're very supportive. I’ve found that she's very supportive of law enforcement.”

DeValkenaere’s conviction — the first in Kansas City history of an on-duty police officer for shooting a Black man — has become a political flashpoint, but it’s also been an unusual case from the outse

Two months after Lamb’s death, KCPD forwarded a probable cause, or PC, statement to the prosecutor’s office recommending a domestic-violence charge against Lamb for slapping his ex-girlfriend that morning, an incident police did not know about until after DeValkenaere had shot and killed Lamb.

It was a highly unusual move, because no prosecution was possible.

“I've never seen that occur,” Picerno said. “So, then the obvious thing that comes to mind is that they did it for political reasons so that the public, the potential juror pool, would know that this was, quote-unquote, ‘a bad guy’ who was the victim here.”

Picerno said the alleged slap wouldn’t have risen to the level of a state case — making it more puzzling why KCPD chose to forward a PC in the case, especially since one witness said Lamb and his ex slapped each other.

“Most likely, that's going to be handled at the municipal-court level,” Picerno said. “... Slaps with no serious physical injury other than a red mark on somebody's face or a welt — that never makes it to state court and, certainly again, I've never seen a dead person charged with a crime.”

KCPD declined to answer repeated questions from KSHB 41 about whether the department typically forwarded cases when the suspect is known to be dead and why such a case would be forwarded.

But in another high-profile case last year, KCPD didn’t forward a PC for consideration of charges when the suspect was dead.

Kevin Moore was suspected of killing two Stowers Institute researchers and setting the apartment on fire to cover the crime.

KCPD drafted a probable-cause statement for those crimes, which it recently released to KSHB 41.

But when Moore later killed another woman and himself in a murder-suicide 15 days later in Clay County, police did not draft a PC nor forward the case to Clay County prosecutors because he was dead.

Additionally, KCPD also refused to provide a PC in DeValkenaere’s shooting of Lamb when the prosecutor’s office requested one.

Major Greg Volker emailed Jackson County Assistant Prosecuting Attorney Dion Sankar three months after the shooting indicating that KCPD would cease cooperating with the prosecutor’s office.

“I just wanted you to know that KCPD is not going to submit a PC nor 327 on this investigation. This was discussed with Chief (Rick) Smith and Deputy Chief (Mark) Francisco,” Volker wrote in a March 23, 2020, email.

That decision forced Baker to take the case against DeValkenaere to a grand jury, a departure from how criminal cases are typically handled in Jackson County and other Missouri state courts.

“It's extremely unusual (for police not to provide a requested PC) and, unfortunately, it's only happened with officer-involved incidents,” Picerno said. “Unfortunately, under Chief Smith, the former police chief, the relationship with Jean Peters Baker became adversarial and he was just refusing — in any kind of an officer-involved incident — to provide her with a probable cause statement. Therefore, she was unable to do her job as an elected official, as an elected prosecutor for Jackson County, to make a determination based on the law of Missouri and the facts as to whether a crime had occurred.”

DeValkenaere testifies before grand jury

After hearing evidence related to Lamb’s shooting in June 2020, a Jackson County grand jury indicted DeValkenaere for first-degree involuntary manslaughter and armed criminal action.

In another irregular circumstance, Baker’s office allowed DeValkenaere to testify before the grand jury, which is not required.

“In my 30 years of being a lawyer, I've not had one client ever requested to go and appear before a grand jury,” Picerno said.

A source familiar with the case who is not authorized to discuss the case publicly said Baker’s office allowed DeValkenaere to testify in the absence of a PC, which a law-enforcement official typically would read to the grand jury to summarize the case against the prospective defendant, because of the unique circumstances of how KCPD approached the investigation and court proceedings.

In the absence of a PC, Baker’s office gave DeValkenaere a chance to offer his side of the story to the grand jury.

“It flies in the face of those who say that Jean Peters Baker was not fair to him, because she gave him the benefit that she doesn't give to any other criminal defendant,” Picerno said.

The case hinged on whether DeValkenaere and his partner, fellow KCPD officer Troy Schwalm, violated Lamb’s constitutional rights by illegally entering the property before he was shot and using excessive force in killing him.

Jackson County Circuit Court Presiding Judge J. Dale Youngs ruled that DeValkenaere didn’t have a warrant, probable cause of permission to enter the property.

Moreover, Lamb had a right to defend himself under Missouri’s Castle Doctrine and Stand Your Ground laws when the officers illegally entered his property with guns drawn, according to Picerno.

“For Detective DeValkenaere, what it does is it makes him an intruder and, as an intruder, he is deemed to be the initial aggressor,” Picerno said. “And in a shooting if you are the initial aggressor, you're not allowed under the law to declare self-defense or defense of a third person.”

Youngs ruled that, under the U.S. Constitution and Missouri law, Lamb was entitled to certain rights and protections, which DeValkenaere ignored and violated before the deadly encounter.

Special treatment for DeValkenaere?

After DeValkenaere was indicted, he was allowed to self-surrender to police, which Picerno said “doesn’t always happen” but added that it’s not unprecedented.

DeValkenaere also self-surrendered after his bond was revoked when the appeal decision came down, choosing to go to jail in Platte County before he was transferred to state prison instead of waiting for Jackson County deputies to arrest him or surrendering in Clay County.

Again, not all defendants are afforded such an opportunity, but the more glaring example was special treatment was that KCPD, when asked for a copy of his initial arrest mugshot, said the department did not take one when processing DeValkenaere, a stark departure from normal procedure even when a former president is arrested.

“I don't know of another defendant — again, I go back on my 30 years of experience — that does not have their mugshot taken,” Picerno said.

DeValkenaere didn’t have a mugshot taken until he surrendered to Platte County authorities nearly 3 1/2 years after his initial arrest and nearly two years after his conviction.

That’s in part, because Youngs allowed DeValkenaere to remain free on bond during the nearly two-year appeals process, a decision even Youngs admitted was unprecedented.

“I would say 99% of the time in Jackson County, when people are convicted after a trial, they do not get an appeal bond,” Picerno said.

Convicted defendants usually are taken into custody at sentencing or shortly thereafter.

Judges, and only judges, decided DeValkenaere’s fate

At trial, DeValkenaere waived his right to a jury and instead had Youngs rule from the bench. But that also left Youngs — who Picerno described as “a very good jurist, a very serious person” — to rule on the complexities of Fourth Amendment law rather than laypersons on a jury.

Youngs ultimately found DeValkenaere guilty of second-degree involuntary manslaughter, determining he was negligent rather than reckless, and armed criminal action — a verdict the Missouri Court of Appeals for Western Missouri affirmed on appeal.

“Judges are human and sometimes they misinterpret the law and get it wrong, but, thus far, no appellate court has suggested that Judge Youngs erred in his ruling,” Picerno said.

The appeals court met Thursday for its monthly conference, the first opportunity to consider DeValkenaere’s Motion for Rehearing, which was filed after the conviction was upheld.

It’s unclear when the appeals court will rule on the motion, but DeValkenaere’s attorneys also applied for transfer to the Missouri Supreme Court.

“We'll have to wait and see if the Missouri Supreme Court decides to take the case and then we'll have a definitive answer,” Picerno said. “But, as of right now at least, it looks like Judge Youngs has applied and interpreted the law appropriately.”

Picerno added that it would be unusual for a criminal conviction to be overturned by the Missouri Supreme Court, though anything is possible.

“It's highly unlikely that any conviction will be overturned when it gets to the Supreme Court,” Picerno said. “I don't know what the percentages are, but I'm guessing probably 98 to 99% of cases that make it to the Supreme Court are upheld.”

He said everyone should welcome the chance for the Missouri Supreme Court to weigh in.

“That's the reason we have a Supreme Court,” Picerno said. “We have a Supreme Court to interpret the laws of the state of Missouri and to make sure that they were followed through and that the facts of the case and the law was applied to the facts correctly. That's their job and their function. I don't have a problem with them reviewing a case one way or the other to make that determination. That's their job.”

Outspoken Baker

Before the grand jury was impaneled, Baker made her first forceful statement about the case in mid-May 2020, releasing a copy of a letter she sent to Smith, the since-retired KCPD chief of police, that voiced her displeasure about the investigation.

She took exception to KCPD’s decision to allow one of DeValkenaere’s former supervisors — since-retired Sgt. Richard Sharp, who maintained a close relationship with DeValkenaere — to oversee the investigation.

Picerno called such an arrangement “extremely troubling.” He added, “There's an inherent conflict of interest there. It's the main reason why we now have the Missouri State Highway Patrol conduct all the investigations in any kind of an officer-involved incident.”

Baker’s letter also criticized Smith’s decision not to provide PC statements in self-investigated officer-involved incidents and the posthumous charges sought against Lamb.

But other than announcing the charges after DeValkenaere was indicted, Baker has remained largely silent until she sent the letter to Parson in June 2023 urging him not to preemptively issue a pardon while the appeals process played out and had her office join the appeal when the Missouri AG’s office declined to defend the verdict.

“I think the people who would allege that (Baker has politicized the case) feel as though law enforcement can do no wrong and they shouldn't be policed themselves,” Picerno said. “So, I do take umbrage with that kind of a statement regarding her. That's not been my experience with her.”